Note: This article was first published May 17, 1911, in the Jasper (Texas) News-Boy. It reappears as Exhibit G of "The Civil War And Tyler County," by James E. and Josiah Wheat. It is reproduced here as it was published by the Wheat's.

Recollections of the Civil War

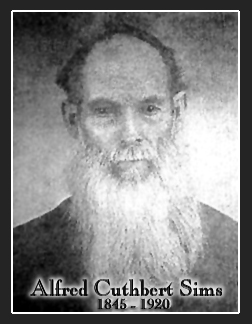

By Rev. Alfred Cuthbert SIMS

To the Jasper News-Boy: As war stories are interesting to both old and young, I will endeavor to give your readers my personal experiences in the Civil War, prefacing the same with a brief sketch of my early life.

I and a twin brother were born in the Republic of Texas on the 5th day of April, 1845, eight miles east of Woodville in Tyler County. We were brought up in the wild forest of East Texas where the scream of the panther, the howl of the wolf and the squeal of the razor-back in the fond embrace of bruin were not uncommon things.

Our mother was very careful to dress us alike and give us equal Privileges in everything. We played together and worked together; and the waters abounded with fish and the forest with game and we enjoyed life "hugely."

We received an education in the country school mostly, which however, I consider were a better grade than our modern rural schools, especially when viewed from a disciplinary standpoint. But all our pleasures were destined to have an end.

The war came on, which disturbed the peace and happiness of all of the families of the South, and I might say of the nation. There were recruiting officers in the land calling for men to join the army and my twin brother, Albert Hubert Sims, although under age, quit the school room at Woodville and volunteered to join the 13th Texas Regiment which was then in Arkansas. This was in October, 1862.

I endeavored to disuade him from his purpose and told him that if he would wait until spring I would go with him anywhere he might wish, but he would not consent. I told him that if he went into Arkansas that late in the fall he would die before spring. His reply was that he did not care if he did. He was determined to go.

No prophet spoke more truly than I on that occasion, for on the 19th day of February, 1863, he died in a hospital at Little Rock, and at that which has ever since made the name of Little Rock of interest to me.

I was so crazed with grief for him who had been my constant associate from infancy that I resolved to go to that then seeming far off land Virginia to fight the battle of my country.

It was the 13th day of April, 1863, a date never to be forgotten by me while my memory lasts, that I bid farewell to my mother, sister, home and friends, and set out in company with a soldier who had been home on furlough, and a third man who was to accompany us as far as Alexandria, La., to take our horses back.

It was a beautiful spring morning and birds were singing as merrily as if there were no war. I remember well as we passed through the Neches River swamps how the red may-haws glistened among the green leaves, quite a contrast with what I was soon to see in the bleak mountains of East Tennessee and West Virginia.

"Though the morn may be serene

And not a threatening cloud could be seen,

What can undertake to say

It will be pleasant all the day?"

Especially is this true in April, for on that memorable day in the evening a heavy tempest arose and we stopped for the night with the family of Major Beaty, who lived in the vicinity of east Jasper, and partook of their hospitality.

The next evening we resumed our journey. Nothing transpired worthy of notice, only that we reached the Sabine River and crossed over at Burr's Ferry, and so to make sure of a stopping place, put up there for the night.

The next day our progress was interfered with by swollen streams. When we reached the Anna Bocca Creak or river, whichever one has a mind to call it, it seemed that we would have to call a halt, for it was bank full and no bridge or ferry. However, on going up stream a little way, we found a raft, which Sibley's brigade, which had lately passed that way had constructed to ferry their baggage over. This we used to take saddles and baggage over and swam our horses across. The third night we stopped at an inn sixteen miles east of Alexandria.

We reached the city the fourth day before noon, turned our horses over to the man to take back, and procured lodging until a boat should be going down the river.

After waiting two or three days we took passage on the steam boat "Homer" down the Red River to the mouth of Big Black River, thence up that stream to Trinity. The levee on the Mississippi having been cut by the enemy, the whole country was enundated and the only means of travel was in skiffs or row-boats. My comrade and I, with a half dozen others, hired two men with a boat to carry us through the overflow and Lake Concordia to Vidalia on the Mississippi, a distance of twenty-five or thirty miles. Late in the evening, while on the lake, a heavy rain with brisk norther sprang up and the boat was in danger of being sunk. We had (to) pull for the shore. We landed at a plantation on the southern shore of Lake Concordia and applied to the overseer for shelter, but he refused us. We then went to the Negro quarters and chartered a cabin for the night, hiring them to move in with another family. We made a fire and dried our clothes and warmed ourselves, and had a very comfortable night for old soldiers.

Next morning we returned to our boat and resumed our journey down the lake to its southern extremity, where we disembarked and walked to the bank of the "Father of Waters."

The enemy were in possession of the river and were constantly patrolling it with gunboats, so there were no ferry boats kept for accommodation of travelers, and we had to hire two Negroes to take us across in a yawl or fisherman's boat. It was with fear that we launched out on the bosom of the mighty water, and that fear was considerably heightened when the boat came near dipping water in the middle of the river. However, we landed safely on the other side in Natchez, and I and my comrade left the squad that we had been journeying with for two days and resumed our march on foot, expecting to have to walk to Brookhaven, Miss.

As we were passing through the city a lady called to us from the balcony of an upper story of a residence and asked: "Where are you from?" And being informed, again she asked : "Where are you going?" We replied, "To Virginia." She replied, "Ah, poor boys! Poor boys!" We continued to journey for sixteen miles and stopped at the residence of one Dr. Johnson, who kindly took us in for the night.

(Rev. Sims continues his description of his trip to Richmond by foot, rail, steamboat and wagon.)

From Montgomery we went to West Point, Ga., to Atlanta, Dalton, Knoxville, Tenn., Bristol, Lynchburg, Va., and to Richmond where we arrived on the 6th day of May, and having learned that Hood's Brigade would arrive in that city in a day or two, we decided to wait until its arrival.

We deposited our baggage at a place called the Texas depot, a place where all the belongings of the Texas Regiment of Hood's Brigade were kept, or any supplies sent there from home were stored; there being a man appointed to see after them. We took a stroll around the city and on our return found that everything I had, except what I had on, had been stolen; which perhaps, was best for me, as my mother had prepared a great bundle of nice warm clothing for me, which would have been too great a burden for me to carry on the long, wearisome marches I was destined to make.

While walking up main street who should I meet but my brother, Lieutenant T. R. Sims, who had been captured at Arkansas Post, carried up north and kept in prison for about four months, had been brought around to Fortress Monroe and exchanged, he with several others of my old friends. His first words to me were: "Cub, what are you doing here?" I told him I had come to the war. His next words were: "Where is Hub?" (Hubert) I replied that he was dead.

I then met several of my old friends, officers who had been in prison with my brother, and in order that we might be together we chartered a room in the American Hotel, where we remained eating and drinking for two days, talking over our trials.

On the 8th day of May Hood's Brigade arrived in the city from Suffolk, down on the Blackwater on their march northward, and as they marched up Main Street I stepped into the ranks of Company F, First Texas Regiment, another memorable day.

Our first encampment was at Frederick's Hall where we remained for several days. We again took up our march northward and crossed the Rapidan River at Raccoon Ford and again camped. From that place we proceeded to Culpepper Courthouse. While there, one day we were ordered to march out south of town to the top of a mountain, where we threw up breast-works of stones that abound in that place, in a day or two it proved a false alarm and we returned to our former camping ground. Again we were ordered on a forced march down the Rappahannock with the news that the enemy was crossing the river, which, too, proved to be a false alarm.

It was while on this march that Gen. Robertson and staff came riding by and a soldier, weary with marching, exclaimed, "Rest, Polly." Gen. Robertson reigned up his horse and said, "Who was that who called me Polly?" So the captain had to tell and General Robertson said, "Put six guns on and make him carry them till night." The order was obeyed.

On one occasion on dress parade Gen. Hood remarked that Gen. Robertson reminded him of his "Old Aunt Polly" and from that all of the soldiers got to calling him Aunt Polly, to the great annoyance of Gen. Robertson.

That night Gen. Robertson gave orders that no fires be kindled, although the air was chill, we were not allowed to make any fires. Next morning some of the boys of Company F, thinking that the order had expired, made a fire to make some coffee for which Gen. Robertson placed Capt. S. A. Wilson under arrest for disobeying orders, and did not release him until we were ready for action at Gettysburg. This proved to be another false alarm. We returned to Culpepper Courthouse.

A few days after this Hood's division was ordered out east of Culpepper Courthouse to a great meadow where Stewart's division of cavalry were to parade with a sham battle between Stewart's cavalry and Hood's infantry. The cannonading was so heavy that the enemy sent out scouts from across the Rappahannock to learn who were fighting.

Again we returned to our old camping ground at Culpepper Courthouse, where we remained until the sixteenth of June, another memorable day, made so by the number of men who fell with sun stroke as we marched toward the Shenandoah River. It was frightful indeed to see so many men falling by the roadside. Under every shade tree men were lying senseless, overcome by the heat. Whether they ever recovered or not, I do not know, as we could not wait to see.

We crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains at Asby's Gap and came to the Shenandoah River which we waded near Berryville, and turned eastward and passed by Winchester and Martinsburg and came to the Potomac River at Williamsport, which we crossed, also waded it. We marched to Hagerstown, Maryland, and from there to Greencastle and Chalmersburg, Pa., where we encamped on a large creek north of the town for some days.

While in the city of Richmond, I was walking around seeing sights, by chance I stepped into a bookstore and the man behind the counter asked me if I would like to have a Testament, at the same time offering one to me. I told him, "No, I did not care for it." He said, "I'll give it to you if you will have it." I told him that if it came as cheap as that I would take it along. And when in camp and times grew dull I would take out my Testament and read, and soon became very interested in it. The old soldiers would eye me, and at last one of them remarked, "Young man, you have come here to die." "But why do you say so?" He said that "no man ever comes here and begins reading the Bible but that he soon dies or is killed in battle." I told him that I was not superstitious enough to believe that reading the Bible would cause me to die or be killed, if true that I had come here to die, it is well that I should prepare for it, so I shall continue to read it, for it teaches us how to die as well as how to live."

We received orders on that morning of the first of July to get ready to march without delay. Everybody was in a stir in camp, rolling up blankets and fly tents, gathering up cooking utensils, bucking on cartridge boxes, etc. We were soon in readiness and marched back through Chalmersburg and took the road toward Gettysburg.

Tramp, Tramp, all day the boys were marching and alas: it was the last march for many of the poor fellows. We all knew we were marching to battle; as evidence I will relate one circumstance. A young man by the name of Rod Meekling of Company B, First Texas, was whistling gaily as we tramped along, all of a sudden he turned to his comrade and remarked with an air of seriousness, "Boys, I have been through many hard fought battles, but if I get through this one to which we are going, I shall count myself the luckiest man in the world." Need I tell you that he was one of the first to fall after getting to battle. Killed dead on the field.

We continued our march all day under a hot July sun and until night, when we bivouacked on the roadside for the remainder of the night. We did not stack our arms as usual, for we were in the enemy's country and everyone lay with his "trusty companion." News came that A. P. Hill's and Ewell's corps had met the enemy and driven them back six miles and captured 5,000 prisoners.

Early next morning we resumed our march and ere long we began to see the bloody shirts, the men who had been wounded in the previous day's battle and who were able to travel, wending their way back to the old Virginia shores. What effect this may have had on the old soldiers, I know not, but to me, who had never seen the like, it was no pleasing sight to behold. It reminds me of one of the Scriptures which says, "Every battle of the warrior is with confused noise and garments rolled in blood." However, we continued our march for some time, then quitting the road we turned to the right. We soon began to cross ridges of fresh turned earth which hid the forms of those who fell in the previous days fight. Whether friends or foes we did not know; it made no difference then, for all strife had ceased with them forever.

We continued our march until we came to a wagon train drawn up in a camping position, and on the cover of each was marked in large letters, "Ordinance", which meant ammunition and guns, but to me it seemed death. We passed this train a little way and came to a halt and rested and ate our scant dinner, though I had no appetite for eating. The bands would try to play, but the instruments would give a plaintive sound without much music. It was indeed hours of great suspense, we whiled away there waiting for the time of action.

At last Col. P. A. Work, commanding First Texas Regiment, ordered us to fall in line; we then made a right flank movement into a thick wood. We were ordered to load our guns and went a little farther. We were ordered to cap them (in those days we used cap and ball). We then moved out into a field. Riley's battery, that accompanied Hood's Brigade, was there in position ready for action. We took our position on the left and a little in the rear of the battery; the Third Arkansas on our left, the Fourth and Fifth Texas on our right in the order named.

No sooner were we in position than did our cannon open fire through a skirt of timber which lay in our front, which was eastward; to which the enemy replied promptly, knocking out a man here and there. To avoid as much danger as possible, we were ordered to lie down until all were in readiness.

Gen. J. B. Hood, as a division commander, took a position in the front of the First Texas Regiment; Gen. Robertson commanding the brigade. Hood had sent Major Sellers, his aide-de-camp, to Gen. Longstreet for orders, and on his return Hood ordered a detail to throw down a rail fence which lay just before us, and immediately ordered a forward movement, he leading the way on horseback. The whole column moved forward and with one united effort threw the fence to the ground. Hood having passed through the gap made by said detail, we emerged into the skirts of the timber; presently random firing began along the line, but I could see no enemy. Presently a full volley from the Third Arkansas Regiment on our left proclaimed the enemy in sight. We pressed forward to a stone fence, where I gladly would have remained for the remainder of the evening for the protection it afforded us, but not so; we must go forward, and I leaped upon the fence, the rocks giving way and I went head forward down a little slant on the side of a branch. My file leader, seeing me fall, turned back to ask if I were badly hurt, to which I replied that I was not, and arose and soon regained my place.

We pushed forward through a field of timothy through which the minnie balls were hissing. As we came to the brow of the hill, that overlooks the valley at the foot of Little Round Top my gun was knocked from my hand and ten or twelve feet to the rear; I did not turn back to get it, but picked up another that lay before us. I got it choked with a ball and threw it down and picked up another. As we came down a slant by the side of a wood a shell cut off a white oak tree, which made us scatter to keep it from falling on us, but we soon closed up the gap and went forward until we were in the valley where we halted, loaded and fired, the front rank on their knees and the rear standing. We only remained in this a few minutes when we again went forward, when we came to the foot of the hill on which the battery stood there was a momentary confusion. Someone ordered a retreat and we began to fall back, but the order was quickly countermanded and another forward movement.

The Third Arkansas Regiment being hard pressed and began retreating, Col. Work ordered a part of the First Texas to their assistance. Capt. Harding, with drawn sword, urged the balance of the regiment forward. The battery had been silenced, our aim being too accurate for the gunners. At the critical moment Gen. Benning's Brigade came upon the field. The 20th Georgia, not knowing that they were coming to our support, supposing us to be the enemy, opened fire on us; but Geo. A. Branard, being our color bearer, stepped out in an open space and waved our state flag to and fro, who, when they saw, ceased firing until they came to us and rendered good service in aiding us to hold what we had gained, as the enemy made several assaults to retake the cannon they had lost.

Just as it began to grow dark we distinctly heard the Yankee officers give orders for another charge. Gen. Benning being there in person, said, "Now, boys, hold your fire until they come right up, then pour a volley into them, and if they don't stop, run your bayonets into their bellies." But they did not come.

When the firing ceased the Georgians began to lay claim to the honor of capturing the battery, which the Texans disputed; but Benning quieted the dispute by saying, "Ah, boys, those Texans had captured this battery before you were in a quarter of a mile of here."

After the battle was over and all was quiet save the cries of the wounded, there was a requisition made for men to go on picket duty and it fell my lot to go for Company F. I stood two hours on the Vidette Post between the two armies and listened to the cries and groans of the wounded and dying, and to their pleadings for water. One man who lay just in front of me would say, "Oh, pardner, bring me a drink of water. I'll assure you that no one will hurt you." "My leg is shot off or I would come to you. I'll give you a dollar for a drink of water. I'll give you all the money I have for a drink of water." To all of which I made no reply, as I had no water to give and could not leave my post for anything.

I was so fatigued and overcome with excitement, heat of battle, and suffocating smoke, that I had to put tobacco in my eyes to prevent myself from going to sleep on post, when I knew it was death to be found asleep at such a time.

After standing for two hours I lay down among the dead and slept like them until aroused by my comrades at break of day to rejoin our command, which had been removed further to the right during the night and other troops had taken our places.

Before leaving, Capt. S. A. Wilson requested of Col. Work that he, with the help of others, be allowed to move the cannon off the field which we had captured that evening, which they did, except one which the enemy, seeing they would have to abandon, pushed off a precipice down among large rocks, so that they could not get it out.

Gens. Hood and Robertson were wounded early in the fight and Gen. Law of Alabama succeeded Hood, and Col. Work took command of the Texas Brigade.

On the 3rd the battle was renewed with an artillery duel, the heaviest cannonading ever heard on the American continent. The air was alive with hissing bomb-shells and the hills and mountains fairly trembled. Our battery being a considerable distance in the rear, the shot all passed harmlessly over our heads, except two or three shots from our own battery fell short of their aim and wounded two men in Co. F. A courier went in full speed and told our gunners to shoot further, which they did.

About the time the cannonading ceased, news came that a brigade of Yankee cavalry had gained our rear and the First Texas Regiment was ordered to go in double quick time and meet them. My knee was so sore from the fall I had at the stone fence the evening before that I could not keep up with the company, and Captain Wilson told me to stop, which I did and returned to the 5th Texas Regiment. Col. P. A. Work saw me and asked me to stay by him while he lay down to rest, and in case he should fall asleep to awaken him if any attack should be made. I had not been standing there but a few minutes when a minnie ball came whistling by me, and I heard the report of a gun in the distance. Another minute and another ball struck a hickory limb close to my head, when Col. Work said that we had better get back to the breastworks, or that a "d----d Yankee would kill us." From the nature of the ground in our front, the man must have been up in a tree to have seen us.

About this time the battle was raging furiously on our left and from our position we could see our men (Pickett's Division) falling back and we had to retreat to avoid being flanked by the enemy, although there was no engagement on our part of the line.

In the meantime, the 1st Texas had met the Federal Cavalry. They had to deploy as a mere skirmish line to make a front to meet a brigade of cavalry. The Yankees, seeming to be in a state of intoxication, dashed through our line firing right and left. They killed one man in Company A, shooting him through the head, while our boys from behind trees and fence corners with their well directed aim left seventeen dead on the field, among them Gen. Farnsworth, their leader. The Fourth Alabama regiment had been sent to aid the First Texas and it is claimed that some of them killed Gen. Farnsworth, which, however, is a mistake. If there had been any honor in killing a federal general doubtless that honor belongs to the First Texas Regiment. It happened this way: Gen. Farnsworth came dashing up to Corporal A. F. Taylor and demanded his surrender, but Taylor replied with a ball from his Enfield, which took effect in his abdomen just below his belt. The General, looking down, saw his wound, turned his pistol on himself, and shot himself four times and fell from his horse, and if those who came to bury the dead were not personally acquainted with him, they never knew they were burying a general.

If Captain Dan K. Rice is living he can tell something about Gen. Farnsworth's boots. He did not take them off the general, but bought them off a soldier that did, and the fine morocco leather that clothed the feet of a federal general in the battle of Gettysburg, were worn by a Texas captain in the battle of Chickamauga. Captain S. A. Willson and Private T. D. Rock of Company F, having been overcome by heat, sat down just before the regiment met the enemy and when the Yankees ... (attacked they) ... captured them. A few volunteers from the Fourth Alabama regiment and a few grape shot from Riley's battery turned the enemy back and they made their escape around the right wing of Lee's army.

I did not rejoin my company until next morning. I was reported captured, but I was with the Fifth Texas and did not learn where it was until the next day.

Our army fell back into the plain and formed a line of battle where we lay all day on the fourth awaiting the enemy's advance, but they made none. It was like a calm after a general storm, not even a picket gun broke the stillness. At night we built fires of the rails along the lines and began the retreat into Maryland.

We marched all night and next day reached Hagerstown, Md. Lee's whole army had fallen back and formed a line in a crescent shape, each wing resting on the Potomac River. His wagon train and artillery were enclosed thereby protecting them from the enemy.

Stewart's cavalry turned to cowboys and collected large heads of beef cattle, which they brought from out of the enemy's country. I noticed while a herd was passing, two fine milk cows ran into it and were driven out. An old lady came and pleaded with the officers to save her cows, as they were her only means of living, but her entreaties were of no avail, and she fell down on the earth and wept most bitterly. Truly war is cruel.

We kept our position about a week, during which time rations became very scarce. Some of the boys killed an old razor-back sow and boiled it in camp kettles without salt and ate it. We were three days without anything to eat, when an old citizen brought three barrels of flour into our camp, which was issued out and cooked without salt or shortening of any kind, only cold water hoe-cake.

Just at what time the army began recrossing the river I do not know; it is probable that it had been crossing all the time we were there, as the stream had been so swollen by rains that it became necessary to cross on a pontoon bridge, which was at Falling Waters, it would have taken nearly a week to cross, for the wagon train was nearly forty miles in length.

We left our camp at dark on the 13th and marched all night, or rather on our feet all night, as we were not moving more than one fourth of the time. If we sat down, the order would be "close up," and perhaps we would not go five steps before it was "halt," and so it was all night and it was raining. So altogether, it was one of the most wearisome marches we ever had. As before stated, we were on our feet all night and until noon the next day when we reached the pontoon bridge, a distance of seven miles from where we started the night before.

While Hood's Brigade was on the bridge a squad of Yankee cavalry dashed up and fired into the rear guard on the hill and killed General Pettigrew, a North Carolina brigadier. There was a mighty scramble on the bridge to get over, but fortunately, no one was thrown off.

Back again on the old Virginia shore there was much murmuring and discontentment among the soldiers. Some of them vowed they would never follow Lee across the Potomac any more ... .

The next day we had skirmishes with the Yankees in the mountain passes in which Capt. Woodard was severely wounded, from which he died.

The next day while marching along the road about noon, I was suddenly seized with a bilious cramp colic, which drew me to the earth. Dr. Cromby hastened to my relief and gave me some medicine which gave me relief. He then told me to mount his horse and ride across the field to where the regiment had halted for dinner and he would come on, and just as I reached my company the pain returned with such severity that I could not dismount, but fell from the horse. The Surgeon came up and gave all the medicine he thought would do me any good, but it gave me no relief. Dr. John Work, the colonel's father, having heard that I was bad off, came to me and asked if any one had any whisky, to which a lieutenant replied that he had. It gave me relief, but not being in the habit of drinking, it affected my head so that I did not know when we resumed our march. They hauled me for some days, which I knew nothing of, I having high fever and was delirious. Finally, when in the vicinity of Rapidan station, Captain A. J. Rigby secured a place for me to stop at a private residence, a rich old farmer by the name of Sales, lived there. When I came to my senses, a faint recollection of being carried one night came to me, I was lost. I did not know where I was nor who lived there. I was lying by a window and could see that I was up-stairs in a fine house. I was almost dying of thirst, I did not know whom to call; however, I made a noise and a negro boy came up to me and asked me what I would have. I replied that I wanted water. He brought a pitcher and sat it on a table by the bedside, I took it up and drank freely. I then told him I wanted to know who lived there. Being informed, I told the boy to tell the old gentleman to come up to see me, which he did. I told him that I was very sick. He said he knew it and asked if I wanted a doctor. I told him I did if there was one to be had. He replied, his family doctor physician lived one and one half miles from there and he would send a negro for him. The old man and his wife treated me very kindly. After some days, when the army became settled down about Fredericksburg, Captain Rigby obtained a leave of absence for me and came back to see me and brought me some money sent by the Texas Relief Society to defray expenses. As soon as I had regained strength sufficient to board a train I rejoined the Brigade at Fredericksburg.

After being there a week or so we received orders to march to the railroad, and we boarded a train to go to Richmond. General Hood met us at the depot and made us a short speech from the platform, but he did not tell us where we were going, about which there were many conjectures. From there we went to Petersburg and thence to Wilmington, N.C. to Goldsboro and to Kingston, S.C. and thence to Augusta, Ga. and Atlanta. From there we took a train bound to Dalton, Dingold and to Tunnell Hill, where we left the cars and took up a line of march through the country.

We had gone about three miles when General Robertson sent word to Col. Work to send him a bare-footed man. I being bare-footed and convalescent, Col. Work ordered me to report to Gen. Robertson at the head of the brigade, which I did. Gen. Robertson gave me orders to go back to Hood's headquarters at Tunnell Hill and tell the commissary to have three days' rations cooked for the brigade and send them on and that I could remain there and come with the wagons. And then it was that I escaped one of the most bloody conflicts that Company F ever had to encounter. There were only thirteen of them reported for duty on going into battle and ten of them were killed or wounded.

Before reaching the battlefield, Col. Work, being ill, resigned the command of the regiment to Capt. D. Rich. I was there where I could hear the roar of the cannon and rattle of the small arms. I was anxious to learn the fate of my comrades. I started to the battle and one of my company (B. Bradshaw) came out and was shot in the big toe. He said to me, "I tell you there is h--l there ahead, and you have the general's permission to stay out of it and you had better do it."

The battle raged furiously for two days. September 19th and 20th, Saturday and Sunday. Our army gained a great victory, but it was dearly bought. Our brigade fortified and lay there in front of Chattanooga on the east front side of Lookout Mountain for several days.

After we had been there about a month and no demonstration having been made by either side, finally one night about midnight hour the enemy opened fire on us with their artillery. The first shell fell in Company M and wounded two or three men. This aroused everybody and they hastened into the ditches. It was a cold frostly night in October and the chilly air and the excitement made the boy's teeth chatter along the line like rattling dry bones. Captain Todd of Company A, who had been lying with his head toward the enemy, had just sat up on his couch when a second shell came crashing through his pillow and went underneath him obliquely about eight feet into the ground, but did not burst, or it doubtless would have killed him. The next shells fell outside our fortification and did no damage.

Not long after this our brigade was called upon to go across the mountain to dislodge the enemy that were crossing the Tennessee River over there. I had taken chills and fever and did not go with them, but stayed in camp. The boys were not very well pleased with their night fight as they failed to drive the enemy back across the river.

On the 10th day of November we broke camp at the foot of Lookout Mountain to go with Longstreet to Knoxville. I still having chills and fever, and being bare-footed, was sent to the hospital at Marietta, Ga. The 10th of Nov. 1863, is another memorable day to me. I had taken a dose of calomel the day before and had to set out and walk ten miles bare-footed and in mud and water up to my knees in many places to reach Chickamauga Station. It took me a part of two days to make the trip.

When we reached the station we were lodged in an old deserted grocery store until an opportunity to send us off to the hospital, and well do I remember it was at break of day when we marched out to the train, and after arriving there we had to await orders to get aboard. The ground round about there was covered with straw and the frost on it seemed like it would burst my feet. I threw my blanket down and wrapped my feet in it until we were permitted to get aboard, and when on the car there was no fire to warm us and it was late in the evening when we reached our destination, the hospital at Marietta. Here we got some comfort and the doctor in charge, a good hearted fellow, gave us a pair of shoes that some poor fellow had no further use for. I had not been there but a week or more when the battle of Missionary Ridge took place, and there were so many wounded to care for that all who were not bed sick were put in a camp called "Convalescent Camp." I, with many others, was sent there to make room for the wounded. I begged the old doctor in charge to let me go to my company, but he would say that I did not have hair enough on my head to go to camp, it having fallen out from the effects of typhoid fever.

Again I was fleeced at that place, I drew two months' pay, $26, and I was tenting with a stranger and as our blankets were scarce, we slept with our clothes on, and the next morning my purse with its contents was gone. I was always satisfied that my bedfellow got it. Though a small sum, it was all I ever received from the Confederate Government for two years and two months service. I kept nagging after the old doctor to let me return to my command and he finally let me go. But Grant had whipped Bragg and had got possession of the road between there and Knoxville, and when I got as far as Rasca, Ga., I, with other Texans, was placed in a camp called "The Camp of Instruction." Here we endured much suffering from cold and hunger.

We had no tent; we had to build fires and bake on one side while the other froze.

On the first day of January, 1864, we started our command by way of Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia and east to Tennessee. The weather was bitter cold and we had no fire. Some nights we had to dance or keep in motion all night to keep from freezing to death. The ice on the lakes in North Carolina at Weldon and other places was thick enough for men to skate on. We were many days on the trip and when we reached Lynchburg, Va., I was sick and had to be taken off the train and sent to the hospital ... . (Rev. Sims was ill for a long time and eventually was released from the hospital and placed on light post duty.)

I returned to Montgomery and was sent to Columbia, Ga., and from there to Macon, where I was when the end of the war came. I surrendered to General Wilson and was paroled the 20th day of April. I stopped with friends at Forsyth, Ga., for two or three weeks. I took the train for Atlanta, the gate city; which then was but a heap of brick. From there I went to West Point, Ga., and from there to Montgomery, Ala., walking a good portion of the way. From Montgomery I took a boat to Mobile, Ala., and from there to New Orleans on the U. S. Transport Warrior, by way of Lakes Borgue and Pontchartrain to Lakeport. Thence I found a part of Hood's Brigade.

The next day we went aboard the steamship Hudson and set out for Galveston. About daybreak next morning the ship ran on to the bar at the mouth of the Mississippi River in Southwest Pass. After many fruitless efforts to pull it off the bar with tugs, a boat was sent to Fort Jackson and a telegram sent to New Orleans for another vessel.

After waiting about days another steamer (the Exact) came alongside and we were transferred to it, and the next day we came to the blockading fleet off Galveston. After some waiting we were permitted to enter the port on the first ship that entered that port after the war.

When the boys set their feet once more in their native land a Texas yell went from the way-worn boys.

When we entered the city, there was an engine with one or two cars standing on the track. We asked the engineer if he would take us to Houston. He replied that that was a special train for Gen. Kirby Smite, who had gone out to the blockading fleet. We told him we were all generals now. He then said that if we would stand between him and any trouble he would take us, but we would have to wait until he could go to Virginia Point for cars and flats to accommodate us. So he went to work and made up a train of box cars and we were soon off for Houston, where we arrived that night, and the next day the citizens gave us a dinner at the "Old Capitol" after which we disbanded and each set out for home.

(The End)